Architecture

This page contains advanced info regarding XCP-ng architecture.

💽 Storage

Virtual disks on HVMs and PV guests

qemu-dm and tapdisk at startup

When a VM starts, whether it is a HVM or a PV guest, it is always started as a HVM. So during the boot process, the device of the VM is emulated. The process for mapping a virtual device from a host to a guest is called qemu-dm. There is one instance per disk like tapdisk, another process used to read/write in a VHD file the disk data. qemu-dm reads and writes to a /dev/blktap/blktapX host device, which is created by tapdisk and is managed by a driver in Dom 0: blktap.

For each read/write in the VM disk, requests pass through an emulated driver, then qemu-dm and finally they are sent to blktap; since tapdisk is the creator/manager of the blktap device, it handles requests by reading them through a shared ring. The requests are consumed by reading or writing in the VHD file representing the disk of the VM, the libaio is used to access/modify the physical blocks. Finally tapdisk responds to qemu-dm by writing responses in the same ring.

tapdisk & PV guests

The process described above is used for HVMs and also for PV guests (at startup, PV drivers are not loaded).

After starting a PV guest, the emulated driver in the VM is replaced by blkfront (a PV driver) which allows to communicate directly with tapdisk using a protocol: blkif; blktap and qemu-dm then become useless to handle devices requests. Note that system calls are used with two drivers: eventchn dev and gntdev to map VM memory pages in the user space of the host. Thus a shared ring can be used to receive requests directly from tapdisk in host user space instead of using the kernel space.

↕️ Components for VDI I/O

XenStore

XenStore is a centralized database residing on Dom0, it is accessible using a UNIX socket or with XenBus + ioctl. It's also a hierarchical namespace allowing reads/writes, enumeration of virtual directories and notifications of observed changes via watches. Each domain has its own path in the store.

A PV driver can interact with the XenStore to get or set configuration, it's not used for large data exchanges. The store is mainly used during PV driver negotiation via XenBus.

For more information, take a look at:

XenBus

XenBus is a kernel API allowing PV drivers to communicate between domains. It's often used for configuration negotiation. It is built over the XenStore.

For implementation, you can take a look at: drivers/xen/xenbus/xenbus_xs.c and drivers/xen/xenbus/xenbus_client.c.

Generally the communication is made between a front and back driver. The front driver is in the DomU, and the back in Dom0. For example it exists a xen-blkfront.c driver in the PV guest and a blkback.c driver in the host to support disk devices. This concept is called split-driver model. It's used for the network layer too.

Note: Like said in the top section, it's not always the case but we can avoid usage of a back driver, we can use a process in the host user space. In the case of XCP-ng, tapdisk/tapback are used instead of blkback to talk with blkfront.

Negociation and connection

Implementation of a Xenbus driver in blkfront:

static const struct xenbus_device_id blkfront_ids[] = {

{ "vbd" }, // Device class.

{ "" }

};

static struct xenbus_driver blkfront_driver = {

.ids = blkfront_ids,

.probe = blkfront_probe, // Called when new device is created: create the virtual device structure.

.remove = blkfront_remove, // Called when a xbdev is removed.

.resume = blkfront_resume, // Called to resume after a suspend.

.otherend_changed = blkback_changed, // Called when the backend's state is modified.

.is_ready = blkfront_is_ready,

};

In the PV driver, it's necessary to implement these callbacks to react to backend changes. Here we will see the different steps during the negotiation between tapdisk and blkfront. The reactions to changes are made in this piece of code in tapdisk:

int frontend_changed (vbd_t *const device, const XenbusState state) {

int err = 0;

DBG(device, "front-end switched to state %s\n", xenbus_strstate(state));

device->frontend_state = state;

switch (state) {

case XenbusStateInitialising:

if (device->hotplug_status_connected)

err = xenbus_switch_state(device, XenbusStateInitWait);

break;

case XenbusStateInitialised:

case XenbusStateConnected:

if (!device->hotplug_status_connected)

DBG(device, "udev scripts haven't yet run\n");

else {

if (device->state != XenbusStateConnected) {

DBG(device, "connecting to front-end\n");

err = xenbus_connect(device);

} else

DBG(device, "already connected\n");

}

break;

case XenbusStateClosing:

err = xenbus_switch_state(device, XenbusStateClosing);

break;

case XenbusStateClosed:

err = backend_close(device);

break;

case XenbusStateUnknown:

err = 0;

break;

default:

err = EINVAL;

WARN(device, "invalid front-end state %d\n", state);

break;

}

return err;

}

And in the PV driver:

static void blkback_changed (struct xenbus_device *dev, enum xenbus_state backend_state) {

struct blkfront_info *info = dev_get_drvdata(&dev->dev);

dev_dbg(&dev->dev, "blkfront:blkback_changed to state %d.\n", backend_state);

switch (backend_state) {

case XenbusStateInitWait:

if (dev->state != XenbusStateInitialising)

break;

if (talk_to_blkback(dev, info))

break;

case XenbusStateInitialising:

case XenbusStateInitialised:

case XenbusStateReconfiguring:

case XenbusStateReconfigured:

case XenbusStateUnknown:

break;

case XenbusStateConnected:

/*

* talk_to_blkback sets state to XenbusStateInitialised

* and blkfront_connect sets it to XenbusStateConnected

* (if connection went OK).

*

* If the backend (or toolstack) decides to poke at backend

* state (and re-trigger the watch by setting the state repeatedly

* to XenbusStateConnected (4)) we need to deal with this.

* This is allowed as this is used to communicate to the guest

* that the size of disk has changed!

*/

if ((dev->state != XenbusStateInitialised) && (dev->state != XenbusStateConnected)) {

if (talk_to_blkback(dev, info))

break;

}

blkfront_connect(info);

break;

case XenbusStateClosed:

if (dev->state == XenbusStateClosed)

break;

fallthrough;

case XenbusStateClosing:

if (info)

blkfront_closing(info);

break;

}

}

This negotiation is essentially a state machine updated using xenbus_switch_state in the frontend and backend. They have their own state and are notified when a change is observed. We start from XenbusStateUnknown to XenbusStateConnected.

To detail these steps a little more:

XenbusStateUnknown: Initial state of the device onXenbus, before connection.XenbusStateInitialising: During back end initialization.XenbusStateInitWait: Entered by the backend just before the end of the initialization. The state is useful for the frontend, at this moment it can read driver parameters written by the backend in the Xenstore; it can also write info for the backend always using the store.XenbusStateInitialised: Set to indicate that the backend is now initialized. The frontend can then switch to connected state.XenbusStateConnected: The main state ofXenbus.XenbusStateClosing: Used to interrupt properly the connection.XenbusStateClosed: Final state when frontend and backend are disconnected.

The starting point of the initialization is in xenopsd:

(* The code is simplified in order to keep only the interesting parts. *)

let add_device ~xs device backend_list frontend_list private_list

xenserver_list =

Mutex.execute device_serialise_m (fun () ->

(* ... Get backend end frontend paths... *)

Xs.transaction xs (fun t ->

( try

ignore (t.Xst.read frontend_ro_path) ;

raise (Device_frontend_already_connected device)

with Xs_protocol.Enoent _ -> ()

) ;

t.Xst.rm frontend_rw_path ;

t.Xst.rm frontend_ro_path ;

t.Xst.rm backend_path ;

(* Create paths + permissions. *)

t.Xst.mkdirperms frontend_rw_path

(Xenbus_utils.device_frontend device) ;

t.Xst.mkdirperms frontend_ro_path (Xenbus_utils.rwperm_for_guest 0) ;

t.Xst.mkdirperms backend_path (Xenbus_utils.device_backend device) ;

t.Xst.mkdirperms hotplug_path (Xenbus_utils.hotplug device) ;

t.Xst.writev frontend_rw_path

(("backend", backend_path) :: frontend_list) ;

t.Xst.writev frontend_ro_path [("backend", backend_path)] ;

t.Xst.writev backend_path

(("frontend", frontend_rw_path) :: backend_list) ;

(* ... *)

One of the role of xenopsd here is to create VIFs and VBDs to boot correctly a VM. This is the output given when a new device must be added:

/var/log/xensource.log:36728:Nov 24 16:40:24 xcp-ng-lab-1 xenopsd-xc: [debug||14 |Parallel:task=5.atoms=1.(VBD.plug RW vm=6f25b64e-9887-7017-02cc-34e79bfae93d)|xenops] adding device B0[/local/domain/0/backend/vbd3/1/768] F1[/local/domain/1/device/vbd/768] H[/xapi/6f25b64e-9887-7017-02cc-34e79bfae93d/hotplug/1/vbd3/768]

The interesting paths are:

- Backend path:

/local/domain/0/backend/vbd3/1/768 - Frontend path:

/local/domain/1/device/vbd/768

When the two paths are written, the creation of the device connection is triggered. In fact the Xenbus backend instance in the kernel space of Dom0 has a watch on the /local/domain/0/backend/vbd path. Same idea for the /local/domain/<DomU id>/device/vbd in the guest kernel space.

After that the creation/connection can start in tapdisk/tapback. When a new device must be created in the guest, tapback_backend_create_device is executed to start the creation; at this moment parameters like "max-ring-page-order" are written using Xenstore to be read later by the PV driver. Important: only a structure is allocated in memory at this time, there is no communication with the guest, the Xenbus state is XenbusStateUnknown on both sides.

After that the real connection can start, it's the goal of static inline int reconnect(vbd_t *device) in tapback:

-

A watch is added on

<Frontend path>/stateby the backend to be notified when the state is updated. Same idea in the frontend code, a watch is added on<Backend path>/state. -

tapbackis waiting for the hotplug scripts completion of the guest. After that it can switch toXenbusStateInitWaitstate. The frontend can then read the parameters like"max-ring-page-order"and responds using the store.blkfrontcreates a shared ring buffer usingxenbus_grant_ring, so under the hood memory pages are shared between theDomUandDom0to use this ring. Also an event channel is created by the frontend viaxenbus_alloc_evtchnto be notified when data is written in the ring. Finallyblkfrontcan update its state to:XenbusStateInitialised. -

After the last state update,

tapbackcan finalize the bus connection inxenbus_connect: the grant references of the shared ring and event channel port are fetched then it opens ablkifconnection using the details given by the frontend.

References and interesting links:

- Xen documentation: https://wiki.xen.org/wiki/XenBus

- How to write a XenBus driver? https://fnordig.de/2016/12/02/xen-a-backend-frontend-driver-example/

Xen Grant table

The grant table is a mechanism to share memory between domains: it's essentially used in this part to share data between a PV driver of a DomU and the Dom0. Each domain has its own grant table and it can give an access to its memory pages to another domain using Write/Read permissions. Each entry of the table are identified by a grant reference, it's a simple integer which indexes into the grant table.

Normally the grant table is used in the kernel space, but it exists a /dev/xen/gntdev device used to map granted pages in user space. It's useful to implement Xen backends in userspace for qemu and tapdisk: we can write and read in the blkif ring with this helper.

Xen documentation:

Blkif

Shared memory details

Like said in the previous part, when the frontend and backend are connected using XenBus, a blkif connection is created. We know the ring is used in the tapdisk case to read and write requests on a VHD file. It is created directly in blkfront using a __get_free_pages call to allocate a memory pointer, after that, this memory area is shared with Dom0 using this call:

// Note: For more details concerning the ring initialization, you can

// take a look at the `setup_blkring` function.

// ...

xenbus_grant_ring(dev, rinfo->ring.sring, info->nr_ring_pages, gref);

// ...

To understand this call, we can look at this implementation with small comments to understand the logic:

/**

* xenbus_grant_ring

* @dev: xenbus device

* @vaddr: starting virtual address of the ring

* @nr_pages: number of pages to be granted

* @grefs: grant reference array to be filled in

*

* Grant access to the given @vaddr to the peer of the given device.

* Then fill in @grefs with grant references. Return 0 on success, or

* -errno on error. On error, the device will switch to

* XenbusStateClosing, and the error will be saved in the store.

*/

int xenbus_grant_ring (

struct xenbus_device *dev,

void *vaddr,

unsigned int nr_pages,

grant_ref_t *grefs

) {

int err;

int i, j;

for (i = 0; i < nr_pages; i++) {

unsigned long gfn;

// We must retrieve a gfn from the allocated vaddr.

// A gfn is a Guest Frame Number.

if (is_vmalloc_addr(vaddr))

gfn = pfn_to_gfn(vmalloc_to_pfn(vaddr));

else

gfn = virt_to_gfn(vaddr);

// Grant access to this Guest Frame to the other end, here Dom0.

err = gnttab_grant_foreign_access(dev->otherend_id, gfn, 0);

if (err < 0) {

xenbus_dev_fatal(dev, err, "granting access to ring page");

goto fail;

}

grefs[i] = err;

vaddr = vaddr + XEN_PAGE_SIZE;

}

return 0;

fail:

// In the error case, we must remove access to the guest memory.

for (j = 0; j < i; j++)

gnttab_end_foreign_access_ref(grefs[j], 0);

return err;

}

Event channel & blkif

So, after the creation of the ring, when a request is written inside it by the guest, the backend is notified via an event channel, in this case, an event is similar to a hardware interrupt in the Xen env.

The interesting code is here:

// ...

// Allocate a new event channel on the blkfront device.

xenbus_alloc_evtchn(dev, &rinfo->evtchn);

// ...

// Bind an event channel to a handler called here blkif_interrupt using a blkif

// device with no flags.

bind_evtchn_to_irqhandler(rinfo->evtchn, blkif_interrupt, 0, "blkif", rinfo);

When a request is added in the ring, the backend receives a notification after this call:

void notify_remote_via_irq(int irq)

{

evtchn_port_t evtchn = evtchn_from_irq(irq);

if (VALID_EVTCHN(evtchn))

notify_remote_via_evtchn(evtchn);

}

blkfront can then be notified when a response is written in tapdisk using a function in the libxenctrl API:

int xenevtchn_notify(xenevtchn_handle *xce, evtchn_port_t port);

For more information concerning event channels: https://xenbits.xenproject.org/people/dvrabel/event-channels-F.pdf

Steps during write from guest to host

-

A user process in the guest execute a write call on the virtual device.

-

The request is sent to the

blkfrontdriver. At this moment the driver must associate a grant reference to the guest buffer address using this function (more precisely gfn to which the address belongs):

static struct grant *get_grant (

grant_ref_t *gref_head,

unsigned long gfn,

struct blkfront_ring_info *rinfo

) {

struct grant *gnt_list_entry = get_free_grant(rinfo);

struct blkfront_info *info = rinfo->dev_info;

if (gnt_list_entry->gref != GRANT_INVALID_REF)

return gnt_list_entry;

/* Assign a gref to this page */

gnt_list_entry->gref = gnttab_claim_grant_reference(gref_head);

BUG_ON(gnt_list_entry->gref == -ENOSPC);

if (info->feature_persistent)

grant_foreign_access(gnt_list_entry, info);

else {

/* Grant access to the GFN passed by the caller */

gnttab_grant_foreign_access_ref(

gnt_list_entry->gref,

info->xbdev->otherend_id,

gfn,

0

);

}

return gnt_list_entry;

}

If you want more info concerning the persistent feature: https://xenproject.org/2012/11/23/improving-block-protocol-scalability-with-persistent-grants/

The persistent grants are not used in tapdisk.

-

The grant reference is then added to the ring, and the backend is notified.

-

In tapdisk when the event channel is notified, the request is read and the guest segments are copied into a local buffer using

ioctlwith aIOCTL_GNTDEV_GRANT_COPYrequest. So before writing to the VHD file we must make a copy of the data. Another possible solution is to use theIOCTL_GNTDEV_MAP_GRANT_REF+ ammapcall to avoid a copy, but it is not necessarily faster. -

Finally we can write the request and notify the frontend.

The read steps are similar, the main difference is that we must copy from the Dom0 VHD file to the guest buffer.

📡 API

XCP-ng uses XAPI as main API. This API is used by all clients. For more details go to XAPI website.

If you want to build an application on top of XCP-ng, we strongly suggest the Xen Orchestra API instead of XAPI. Xen Orchestra provides an abstraction layer that's easier to use, and also acts as a central point for your whole infrastructure.

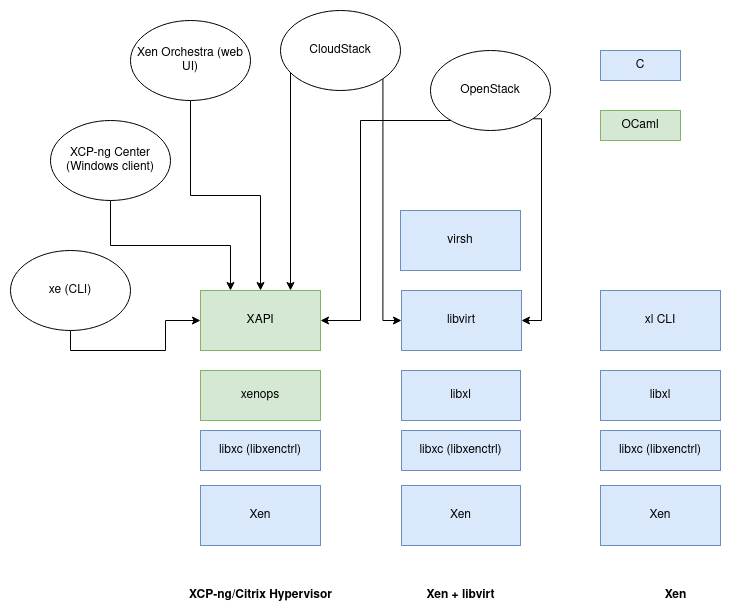

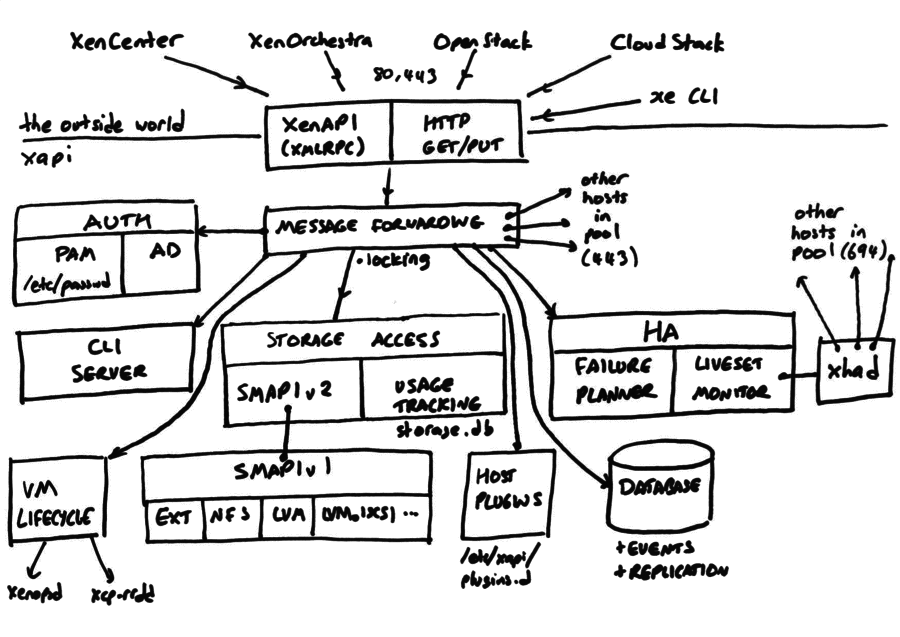

XAPI architecture

XAPI is a toolstack split in two parts: xenopsd and XAPI itself (see the diagram below):

XCP-ng is meant to use XAPI. Don't use it with xl or anything else!

General design

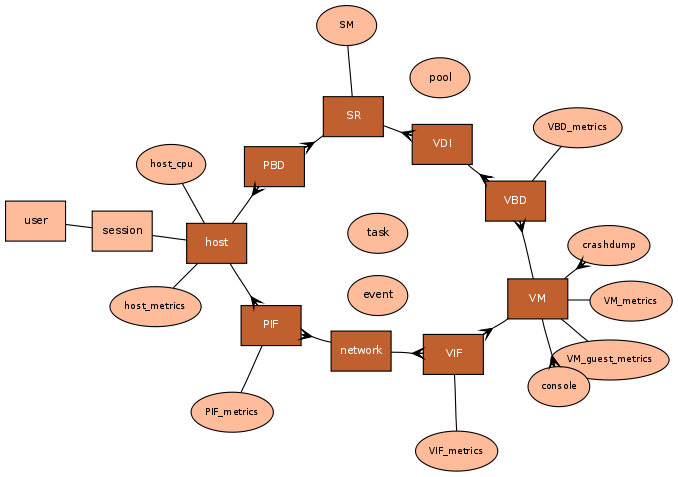

Objects

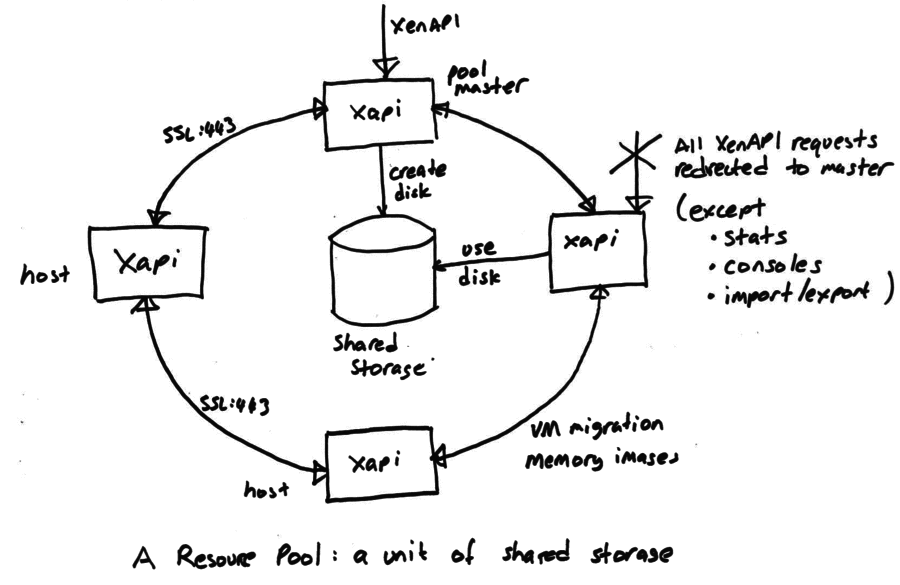

Pool design